Ontology and Semiotics of Memory: Unveiling the Fabric of Recollection

Memory, the cornerstone of our subjective experience, transcends the simple act of storing and retrieving information. It shapes our perception of self, informs our decisions, and colors our interactions with the world. Understanding memory necessitates a multifaceted approach, delving into both its philosophical underpinnings (ontology) and the signifying systems (semiotics) that construct our recollections.

The Ontological Landscape of Memory

The ontological question regarding memory probes its essence: what does it fundamentally mean to remember? One prominent perspective views memory as a representation of past experiences stored within the brain. This internalist view suggests that memories exist independently of the world, accessible only through internal mental processes. However, this position struggles to explain the influence of external factors on memory, such as social cues or historical context.

An alternative perspective, externalism, posits that memories are not solely internal but are distributed across the brain, body, and environment. Proponents like Alva Noë argue that our bodies and the world around us act as mnemonic aids, shaping how we encode and retrieve memories. For instance, the scent of a childhood bakery might trigger a vivid memory of visiting there with family. In this view, memory becomes an embodied and situated phenomenon, inextricably linked to our interactions with the external world.

Another ontological debate centers on the nature of the memory trace. Is a memory a static record of a past event, or is it a dynamic reconstruction shaped by present experiences and biases? The concept of memory as reconstruction suggests that our recollections are not perfect snapshots of the past but rather fluid interpretations influenced by our current perspectives and emotions. This view aligns with the work of psychologists like Elizabeth Loftus, who have demonstrated how memory can be malleable and susceptible to suggestion.

The Semiotic Web of Memory

Semiotics, the study of signs and symbols, offers valuable insights into how memories are constructed and communicated. Memories are not simply neutral representations; they are imbued with meaning through a system of signs. These signs can be visual, auditory, olfactory, or even emotional, forming a complex web that constitutes our recollection.

One key semiotic concept is the signifier, the form that carries the meaning (signified) of a memory. For example, the sight of a faded photograph (signifier) can evoke a flood of emotions and details about the event it depicts (signified). The relationship between signifier and signified is not always fixed; a particular scent might trigger different memories for different people based on their personal experiences.

Metaphors and narratives also play a crucial role in shaping memory. We often organize and communicate memories through stories, weaving them into a coherent narrative that makes sense of our past. These narratives can be influenced by cultural norms and personal biases, shaping how we remember events. For instance, the narrative of a triumphant athletic victory might overshadow the teammate's crucial assist, highlighting the subjective nature of memory construction.

The Intertwined Dance of Ontology and Semiotics

Ontology and semiotics are not isolated concepts; they are intricately intertwined in the realm of memory. The nature of memory (ontology) shapes how we use signs and symbols (semiotics) to construct and communicate our recollections. For instance, if we believe memory to be a static record of the past, we might be more likely to view our memories as objective truths. Conversely, understanding memory as a reconstruction process encourages a more critical appraisal of our recollections, acknowledging the influence of interpretation and bias.

The semiotic tools we use to construct memories are also shaped by our ontological understanding of memory. If we view memory as an embodied phenomenon, we might place greater emphasis on sensory details and the role of the body in memory retrieval. For example, a veteran recalling a war experience might describe the sights, sounds, and smells of the battlefield in vivid detail. Conversely, a purely internalist view might focus on linguistic representations and internal thought processes, neglecting the rich tapestry of sensory experiences that can contribute to memory formation.

The Significance of Memory

Understanding the ontology and semiotics of memory has profound implications for various fields. In education, it highlights the importance of creating multisensory learning experiences that cater to different memory styles. By incorporating visual aids, kinesthetic activities, and opportunities for storytelling, educators can leverage the power of semiotics to enhance encoding and retrieval of information. In law, it underscores the need for careful consideration of the fallibility of memory and the potential for bias in eyewitness testimonies. Recognizing the reconstructive nature of memory and the influence of suggestive questioning techniques can help legal professionals evaluate the accuracy of memory reports. In therapy, it informs techniques for memory reconstruction and trauma processing. By helping patients understand the role of schemas and biases in shaping their memories, therapists can empower them to approach their past with a more balanced perspective.

On a personal level, delving into the nature and construction of memory fosters self-awareness. It allows us to recognize the subjective nature of our recollections.

Beyond the Modern Synthesis: Memory and the Extended Evolutionary Framework

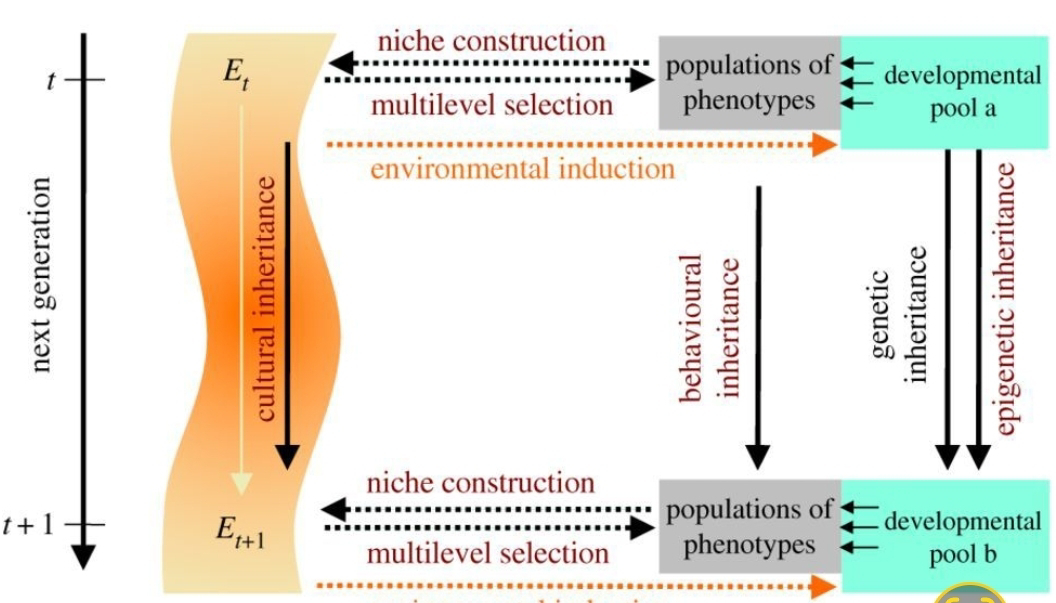

The Modern Synthesis, focuses on genes as the primary unit of inheritance. However, the intricate dance of ontology and semiotics in memory challenges this view. Memories are not solely encoded in genes; the environment and our interactions with it play a crucial role. This necessitates an extended evolutionary synthesis that goes beyond genes.

Imagine a bird learning a song. While genes may provide a blueprint, the specific song learned depends on the bird's environment – the songs of other birds it hears. Similarly, human memory formation is shaped by our experiences and interactions with the world around us. This highlights the need for an extended synthesis that acknowledges the role of culture, environment, and embodied experiences in memory, alongside genes.

The Significance of This Exploration

Understanding memory's ontology and semiotics can have profound implications. Educators can create multisensory learning experiences that cater to different memory styles. In law, recognizing the fallibility of memory aids a more nuanced approach to eyewitness accounts. Therapists can help patients approach their memories with a critical eye, understanding the role of interpretation and bias.

The exploration of memory transcends disciplinary boundaries. By acknowledging the limitations of the Modern Synthesis and embracing an extended framework, we can achieve a more holistic understanding of how we remember – a crucial step in unlocking the complexities of the human experience.

Comments

Post a Comment